Reverend Peter M.J. Stravinskas is the editor of The Catholic Response, and the author of over 500 articles for numerous Catholic publications, as well as several books, including The Catholic Church and the Bible and Understanding the Sacraments.

Editor’s note: The following homily preached by the Reverend Peter M. J. Stravinskas, Ph.D., S.T.D., on February 12, 2019, at the Church of the Holy Innocents, Manhattan.

Beginning yesterday and for the next couple of weeks, at daily Mass the Church will be treating us to passages from the Book of Genesis. This afternoon, I shall limit myself to the first two chapters, given that this is a noontime Mass on a work day.

The first book of the Bible, interestingly enough, is rather a late-comer and shows the hand of several authors and editors. Genesis is the Greek name for the work (meaning, “beginning”), while the Hebrew name comes from the first words of the volume, “In the beginning, God created.” The book may be divided into two principal sections. The first eleven chapters deal with the beginnings of the universe and of human beings in general, while chapters 12-50 are more specific and describe the national origins of the Hebrew people.

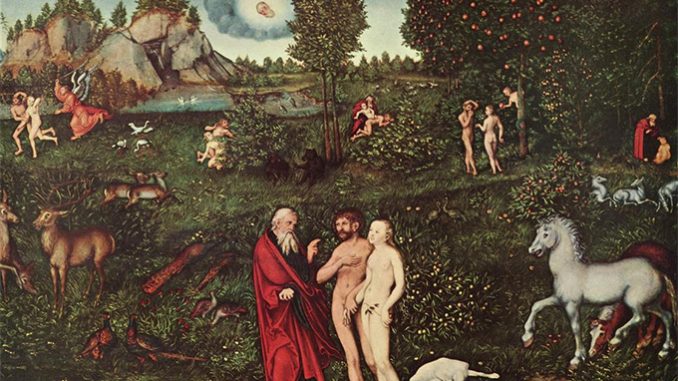

Even a casual reader of Genesis will notice that there are two creation accounts with very different explanations of how things came to be. The first (1:1-2:4a) is from what is termed the Priestly source (because of this writer’s concern with matters liturgical); the second begins at 2:4b and is attributed to the Yahwist (so called because he consistently uses “Yahweh” to name God). Neither purports to be an eyewitness recording of those first events. On the contrary, they are poetic and theological works designed to convey certain basic religious truths – which is why St. Augustine (writing in the fifth century) would caution his readers not to interpret these initial chapters of Genesis literally. Indeed, the apparent inconsistencies of the two accounts (from a contemporary scientific or historical viewpoint) did not upset the final editor, which is why he placed them side by side (in the liturgy, the first version yesterday and today, and the second tomorrow and Thursday). In fact, their theologies complement each other.

The Priestly account is a masterpiece of creative literature. The author divides God’s creative activity into six days, thus foreshadowing what would become man’s work week, because he intends to teach a lesson at the end. He has God rest on the seventh day, providing human beings with a divine example for the Sabbath observance. The creation is carefully arranged in an ascending order. One gets the same feeling as when listening to a symphony: There is a recurring theme; it is embellished and undergoes variations; the piece reaches crescendo in the creation of Adam and Eve and is resolved in the Lord’s Sabbath rest. This account differs from all the primitive creation stories of other cultures and religions in that God creates the world from nothing, in an effortless manner (by a word) and in a majestic style (“let us”). The biblical story highlights the Hebrew conviction that their God is unlike any other god.

Creation occurs through a word. For the Hebrew, a word was a very powerful concept, the very extension of the speaker. Therefore, we can say that God puts Himself into the act of creation. The power of the word is emphasized very often throughout the Old Testament and achieves a new depth of meaning in the New Testament when John’s Gospel informs us that “the Word became flesh.”

The Yahwist account is much older and is written in such a manner that the man and the woman become prototypes of Everyman and Everywoman. It is interesting that here humans are created first. The theological reason seems to be to stress the fact that the entire universe is made specifically for human beings and is at their disposal. This is hit upon again when we read that the man named all the creatures: To name something implied sovereignty over that thing.

The man is created from the clay of the earth and is enlivened by the breath of God. This gives expression to the belief that humans are of the earth, yes, but that they share in the life of God Himself.

In this primitive theology, God is described in very anthropomorphic terms. In fact, it is somewhat amusing to picture God creating all sorts of beings to make the man happy, but to no avail. Of course, even this has a theological purpose, for the author may have been trying to discourage the people of the time from engaging in pagan rites of bestiality. Therefore, the sacred author seizes the opportunity to make this point: Only another human being can properly complete and fulfill a human being. The fact that the woman is created from the man stresses yet another cardinal tenet of the Judaeo-Christian Tradition, namely, that man and woman share a common life and enjoy a God-given equality.

Doubtless, some of you are asking how all this fits or does not fit with the theory of evolution. First, we have to say that there is no one, single theory of evolution but several. In the main, though, we must say that Catholic teaching eschews any purely materialistic view of the origins of the universe and of man. However, it does not require adherence to various forms of creationism. From St. Augustine to Pope Pius XII to Pope John Paul II to Pope Benedict XVI, the Church has staked out a kind of via media. Realizing that the early chapters of Genesis are written in poetry and that the Bible is a theology text and not a science book, the Church is able to navigate a path through the Scylla and Charybdis of materialistic evolution and “young earth” creationism.

So, what must we hold? First, that all that exists is created by Almighty God; second, that there was a special and direct creation of man, done by the spirit or breath of God; third, that every human being coming into the world to the present day is likewise a special and direct creation, being endowed with an immortal soul by God; finally, that all creation is held in existence by the ongoing providential care of the Creator.

Quite appropriately, then, did we join our voices to that of the Psalmist as we prayed: “O Lord, our God, how wonderful your name in all the earth!”